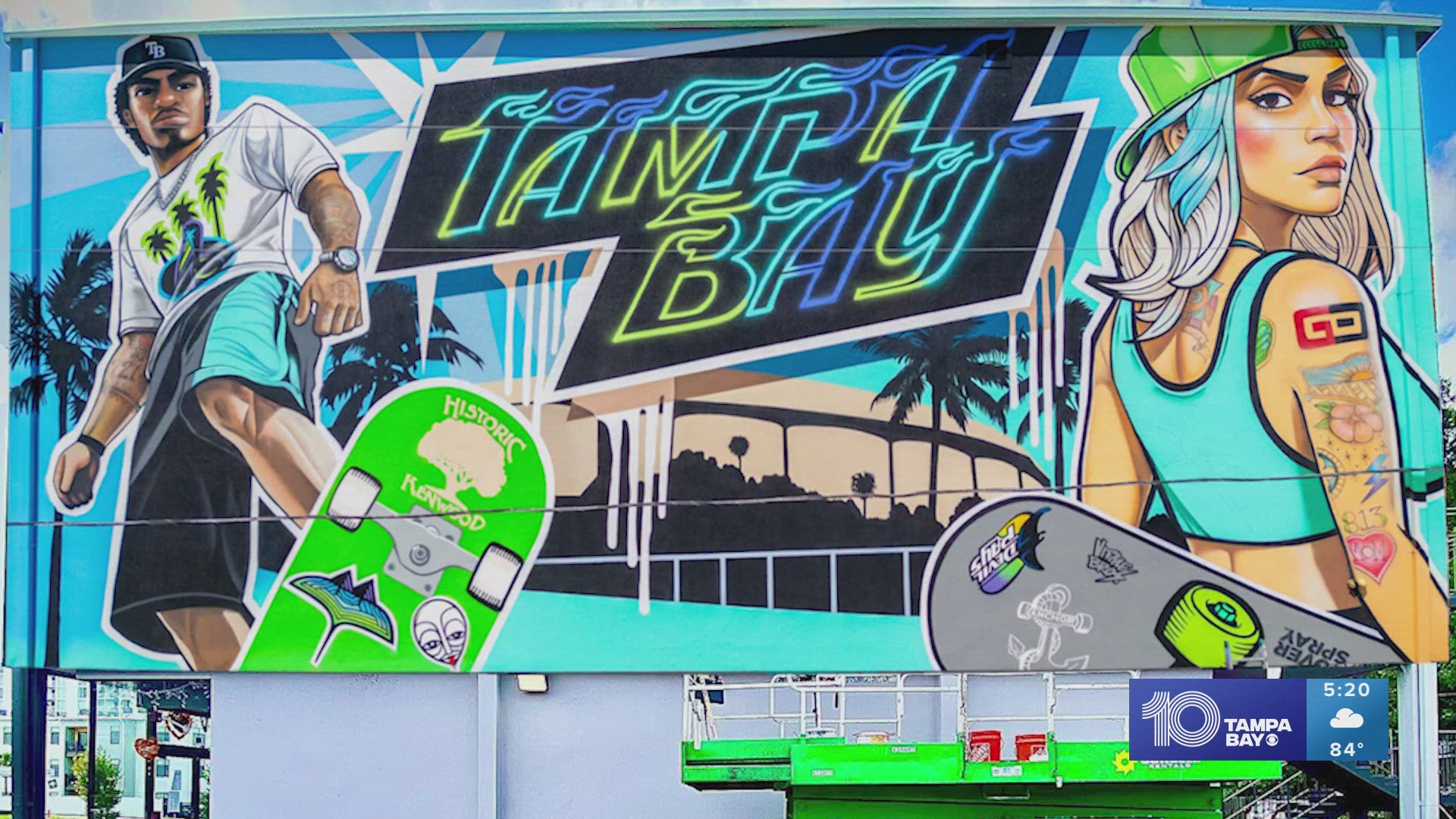

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. -- As the City of St. Petersburg and the owners of the Tampa Bay Rays argue over who will get to keep more millions when the team eventually leaves there is, perhaps understandably, resentment among those forced to give up their homes and businesses 30 years ago to make room the stadium in the first place.

Now, some of those whose lives were uprooted wonder - with talk of the team moving on - was it all worth it?

Lois Grayson remembers fondly the days when her mother-in-law Willie Mae Grayson owned Bill's RonRico Club, a thriving bar and hotel located along Second Avenue in St. Petersburg.

"They told her they were going to build up around there, and she was very jubilant -- very happy for that," said Grayson. "She had her whole building remodeled thinking they were going to upgrade the community and she would be there."

But in 1985, Willie Mae was forced to sell her property to the city, to make room for what was then being called the "Florida Suncoast Dome."

When her building was demolished, Willie Mae's spirit, says Grayson, was also crushed.

"From the moment they took the building from her, she started to die. She died of a broken heart."

Hundreds of people lost their homes and livelihood as the city used its power of eminent domain to make room for what would eventually be called Tropicana Field.

It would sure be nice, says Grayson, if they'd consider sharing some of the wealth it created with the decedents of the displaced.

"But you think they'd do that?" she laughs, "No."

Which is why it may be understandable that Grayson, and others who feel that they were forced to give up so much for so little, would now be somewhat resentful as they watch the Rays and the City of St. Petersburg argue over who should get to keep more of the millions upon millions of dollars that the 85-acre parcel will undoubtedly fetch when the team leaves and the land is redeveloped or a new stadium is built.

There were some who tried to hold out.

Abe Katz refused to sell his grocery store in 1985. Two years of negotiations later, the City of St. Pete finally paid him nearly three times what they had originally offered.

To this day, a café at Benjamin Residential Tower in St. Petersburg is called Katz Korner, named for Katz, who passed away in 2009.

"What eminent domain did not compensate for, and usually still does not, it's for any kind of emotional or sentimental or personal attachment," says Paul Boudreaux, a Stetson Law School professor specializing in property law.

Boudreaux says Florida's eminent domain rules, which St. Petersburg used in the 1980's, have since been tightened so government can no longer forcibly take one person's property only to hand it over to another.

The city could, however, maintain ownership of a new stadium for at least 10 years just as they did with Tropicana Field, then convey the property. But these days, he says, the public would be far more skeptical.

"Even in a situation of say, a baseball stadium that still is owned by the city, they worry: Is this being done to help wealthy individuals? Is government abusing its power?"

Those are questions Lois Grayson can't help but feel should have been asked 30 years ago.

"It was a whole community. We had stores, they had restaurants and all of that. It was just gone. They just took it," she said. "It's over now. But I just wish you could've been different."