400 graves from Black cemetery potentially buried under East Tampa homes, church

The St. Joseph Aid cemetery served Black Americans during the Jim Crow era but has disappeared from records.

Lloyd Sesler said he always wondered what happened to the cemetery along North 34th Street near the Greater Mt. Carmel AME Church in East Tampa.

“We used to travel through it and saw a lot of headstones, but don’t know what happened to them,” he said.

Today, the 87-year-old questions if graves are still there.

Harold Evans remembers seeing the cemetery as a child and wonders the same.

"I never found out what happened to those tombstones...because they started to build homes there," he said.

The East Tampa native said he'd often pass the graves on his way to school. He also remembers his grandmother telling him she buried one of her children there who died at a young age. He doesn't recall her ever saying much more about the cemetery.

For nearly three years, archaeologists have uncovered hundreds of graves from African American cemeteries that have been destroyed and erased across the Tampa Bay area.

The mystery surrounding the St. Joseph Aid Cemetery, also known as the Montana City Cemetery, could lead to the discovery of at least 400 more.

A Rich History The St. Joseph Aid Cemetery was founded by one of Florida's most prominent African Americans in the early 20th century.

“My grandparents are very closed about this, about the whole history,” said Mark Walker, an executive at ESPN.

Walker’s great grandfather, Thomas H. B. Walker, originally owned the plot of land in East Tampa where Sesler and Evans remember seeing graves in the 1940s as children.

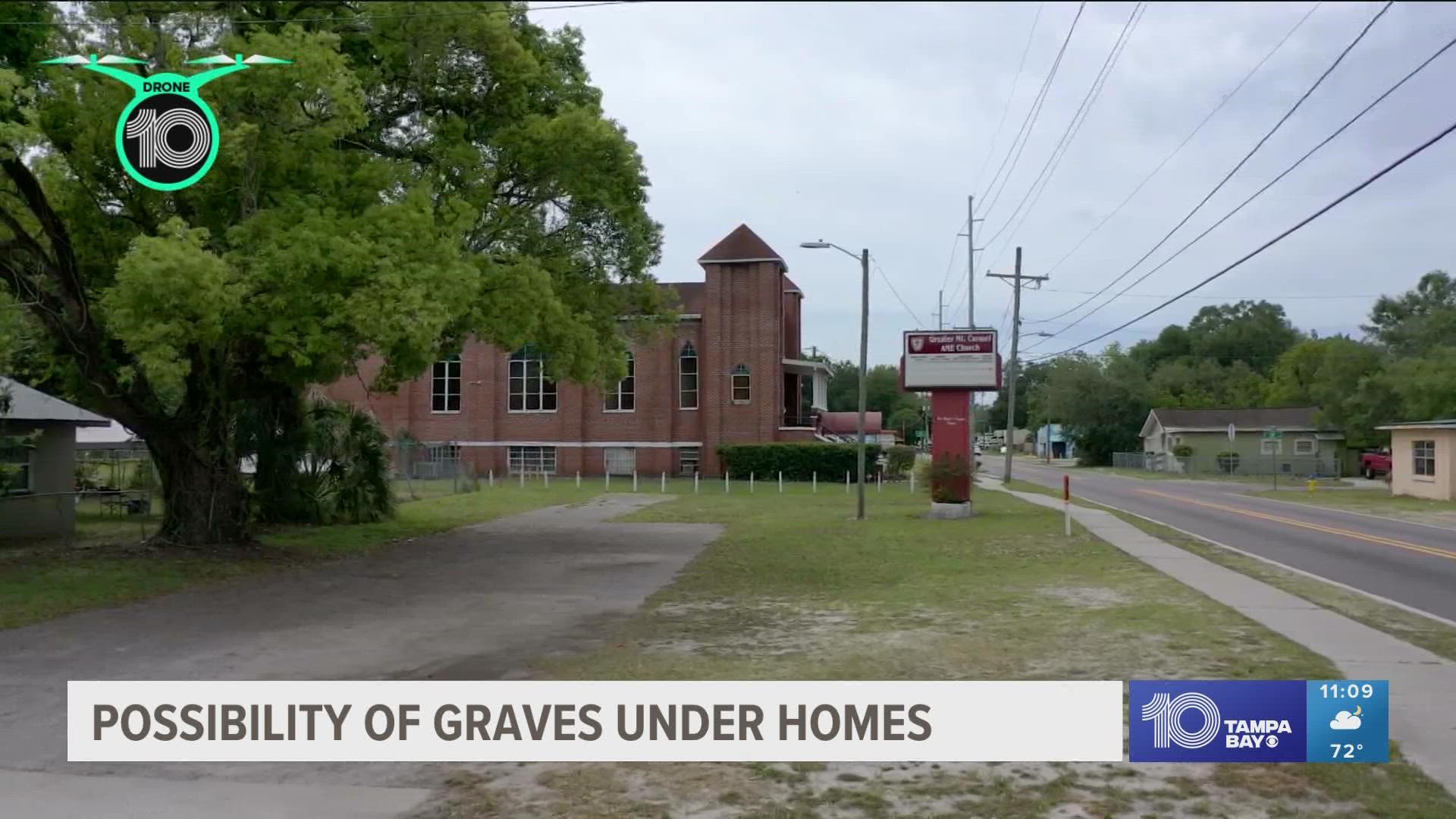

The Rev. Thomas H.B. Walker was a pastor, businessman, civil leader and overall pioneering figure in Florida history. He spent most of his time in Jacksonville, but was minister at the Bowman Methodist Episcopal Church in Tampa from 1907 to 1910, and served as pastor before that.

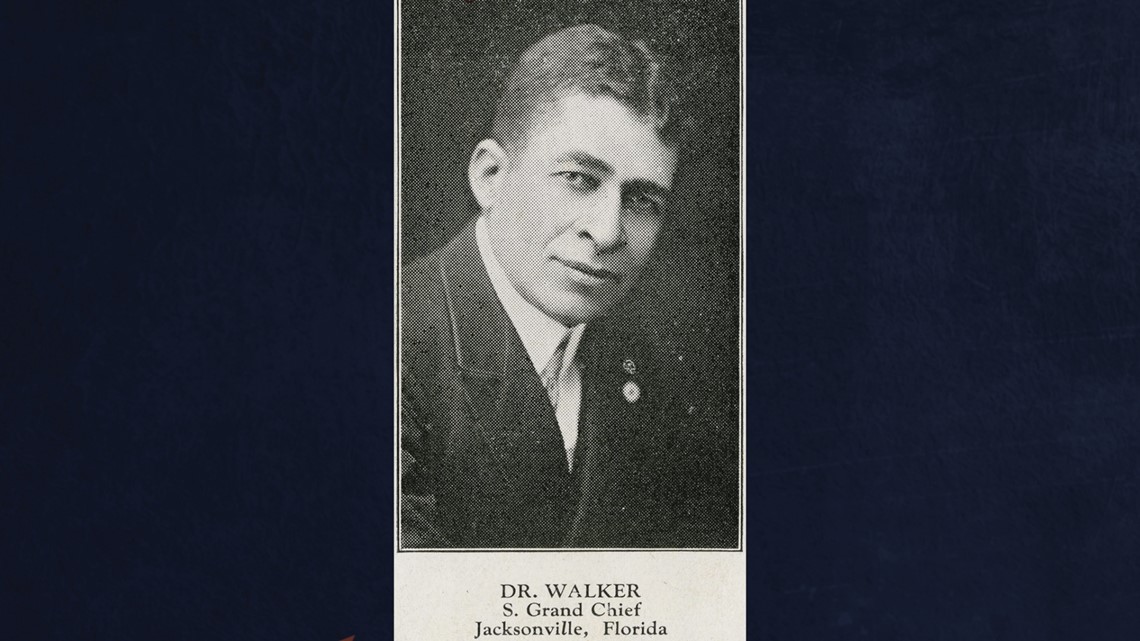

He was also well known as the founder and chairman of the St. Joseph Aid Society, a benevolent organization that served African Americans at a time when white ones excluded them from membership.

At its peak, the St. Joseph Aid Society claimed more than 150,000 members nationwide.

“As I understand it…it's a mutual society, a mutual burial society, which...back then was kind of like an insurance company, right, in the sense that the members contributed to it,” Mark said. “And then when they died and had burial expenses, the aid society would pay for the burial expenses.”

According to the National Humanities Center, African American mutual aid societies offered a range of benefits to its members including insurance that covered illness and burials. The group also states societies promoted education and job training during a time when Jim Crow was the law of the land.

Thomas H. B. Walker worked closely alongside his second wife, Rosa G. Holmes Walker, who was a funeral home director and prominent businesswoman in Jacksonville. Records 10 Tampa Bay reviewed at the University of North Florida show she helped bury hundreds of African Americans throughout Duval County.

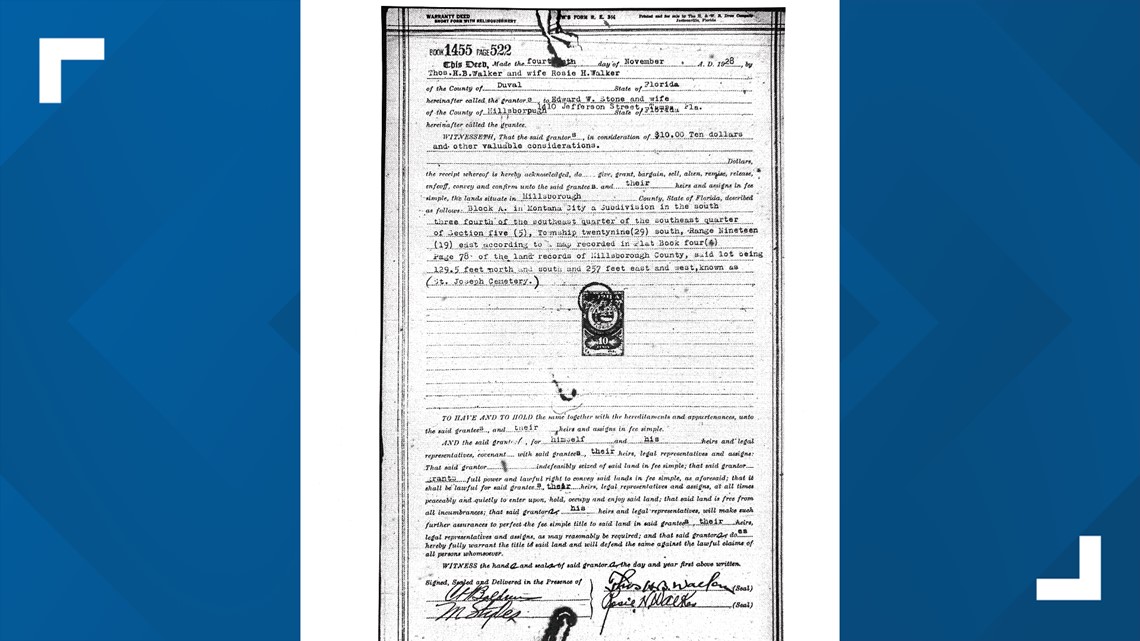

A 1907 deed uncovered by 10 Tampa Bay shows where Thomas H. B. Walker purchased a little more than three-quarters of an acre of land in the Montana City subdivision of Hillsborough County for what would become the St. Joseph Aid Cemetery. Modern maps place the land at the corner of North 34th Street and Genesee Avenue in the Rainbow Heights neighborhood of East Tampa.

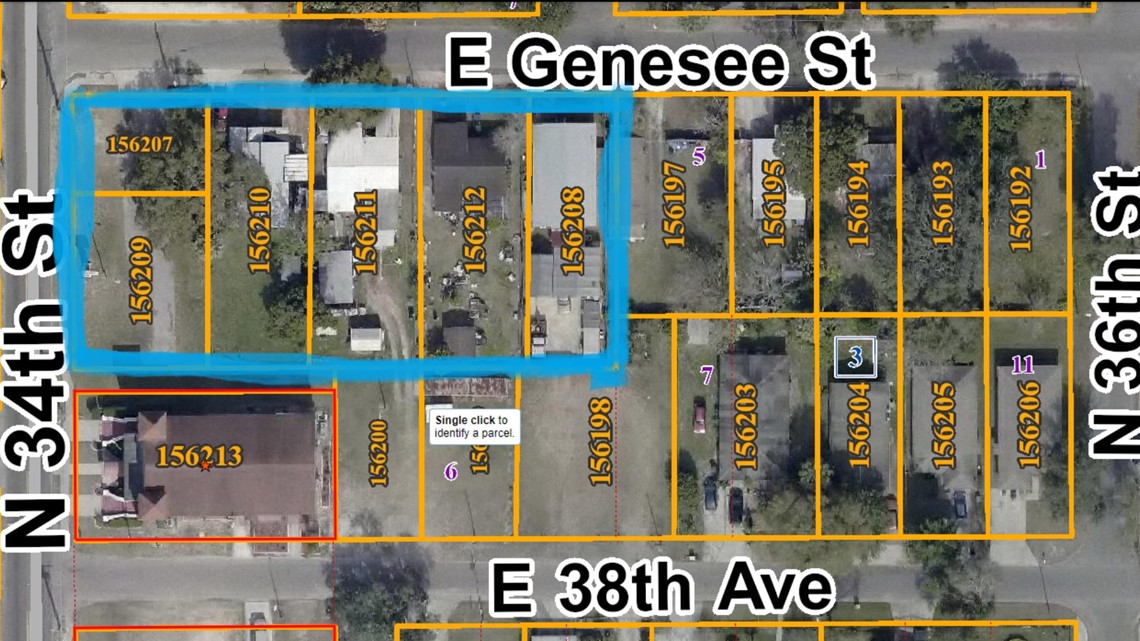

It is roughly the same area where Dr. Erin Kimmerle, a forensic anthropologist at the University of South Florida, has been searching for a cemetery in what old plat maps refer to as the Montana City subdivision. There are also a handful of death certificates that reference a cemetery in the Montana City neighborhood.

“Looking through the records and having seen the deed for this space that lists St. Joseph’s Cemetery, I think it is the same as Montana City Cemetery,” Kimmerle said.

Stone Funeral Home was listed on many of the death certificates 10 Tampa Bay uncovered after receiving an initial list of St. Joseph Aid burials from Ray Reed, a former Hillsborough County worker whose research on erased Black cemeteries in Hillsborough County has triggered a number of archaeological searches.

A 1928 deed shows where Thomas H. B. Walker and his wife transferred the property to the funeral home's owners: Edward Stone and his wife, Fannie. The multi-generational family business is still in operation today.

“I’m concerned about the families that still have families there,” Fannie B. Stone II said, president and owner of Stone Funeral Home.

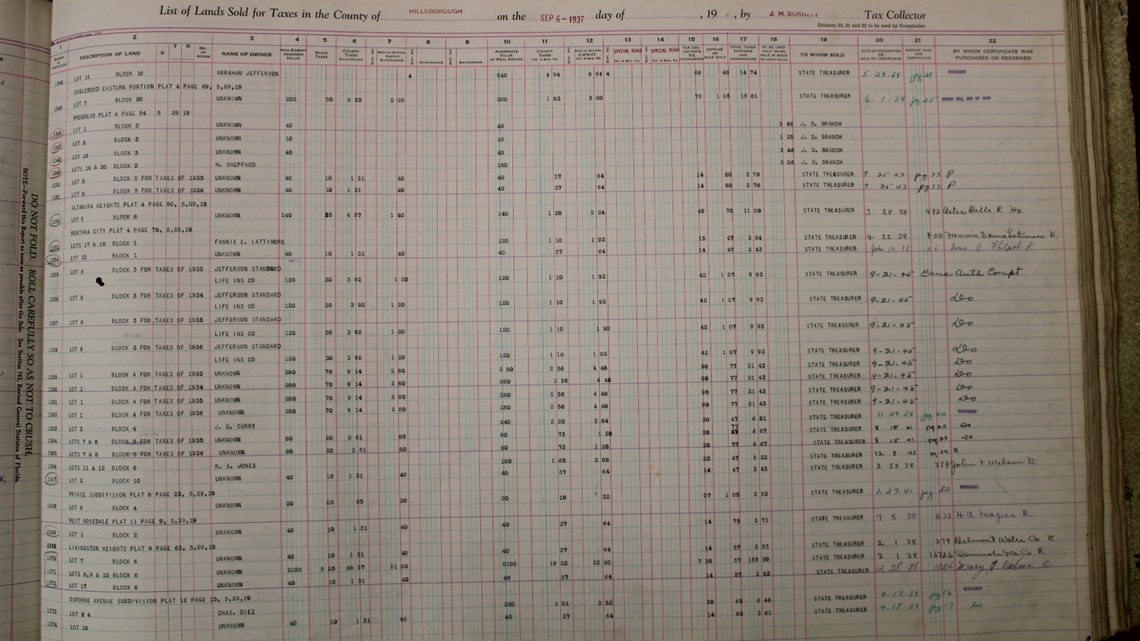

Disappearing Act Records show the cemetery land was eventually sold over taxes, although cemetery land isn't typically taxed Subtitle here

Although burials continued through at least 1940, records from the Department of State show in 1937, the state sold the land to the treasurer's office for unpaid taxes, even though cemeteries are usually exempt from taxes.

The owner was listed as unknown.

"We were saying we didn't know that we paid taxes on cemeteries," Stone II said of what was once her family's land.

Today, the Greater Mount Carmel AME Church parking lot and four homes cover the property. The land was eventually sold, reparceled and redeveloped, with the first home built in 1924. The remaining three homes were built in 1956 after burials stopped in the cemetery around 1940.

“This is my first time hearing of it,” said Amado Pedroso, who was raised in the area and lives in one of the homes on Genesee. He said knowing of other erased Black cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area like Zion and Ridgewood makes him believe graves could still be under his home and others.

“They ain’t just gon' put it there and then it ain’t there,” he said.

Reed initially raised awareness to 10 Tampa Bay about burials at St. Joseph Aid.

His research, along with that of Dr. Kimmerle and 10 Investigates shows there were at least 400 burials at St. Joseph Aid Cemetery from the early 1900s through about 1940.

Kimmerle says it is unlikely the graves were ever moved.

“There’s no evidence of that, and I would say that’s true for all of the sites that we’ve been looking at,” she said, adding that a court order and family permission would have been required to move the graves, and that is a costly and cumbersome process.

“I think the actual moving of graves from one site to another might have happened on individual levels here and there. You know, certain families may request that, but wholescale in terms of a cemetery, I think it’s very rare,” she said.

In other cases of erased Black cemeteries across the Tampa Bay area, recent archaeological digs proved that graves were not always all moved, even if historical documents said they were.

"It's just so sad how it was desecrated by people who did not have any feeling for these people that was buried in these Black cemeteries. It's very sad to know this," said Evans.

A Grave Dilemma Determining if graves are still on the property could be costly.

Although a deed, death certificates and oral histories confirm the St. Joseph Aid cemetery did exist along North 34th Street, two things stand in the way of discovering if graves remain: access to private property and costs to cover an archaeological search.

Florida state law protects all human remains, but private property owners aren’t obligated to grant access to their property for searches.

State Rep. Fentrice Driskell worked on a bill that would have granted the state an easement on private property in cases where there is credible evidence of burials. However, as the bill moved forward, that part was taken out.

“Florida has very strong property rights. Anytime that you are giving the government more rights, I think people get suspicious of it,” she said.

Driskell said she hopes to reintroduce that part of the bill again in an upcoming legislative session.

While that bill addresses the search and discovery of graves, it’s unclear what action lawmakers will take for property and business owners living and working on destroyed cemeteries.

“That’s a really tricky one,” she said. “Maybe we didn't spend as much time talking about the compensation for the property owner…The property owners already have such strong rights, but what about the descendants?”

The impact on descendant communities is emotional and economic. Rachael Kangas, an archaeologist with the Florida Public Archaeology Network at the University of South Florida said most initial searches begin with using ground-penetrating radar, and property owners typically cover the bill. She said the cost can run several thousand dollars, which can be cost-prohibitive.

Additionally, the discovery of graves could drive down property values for homeowners in an area.

"I think you really have to consider what is the right thing to do," Driskell said. "And when you have this descending community that's looking for their loved ones, the right thing to do would be to allow for something non-invasive like ground-penetrating radar to try to find out if those graves are really there."

Living with loss Researchers say racism and predatory land practices contributed to the demise of African American cemeteries and institutions.

Mark Walker said the theme of loss is a tragic part of the American story for descendants of slaves and one that is not unique to Tampa.

"It's typical...like in Tulsa that...a lot of times there [is] this kind of revolt of the white community against Black entrepreneurs or Black folks that have actually accumulated something," he said, referring to the 1921 Tulsa race massacre that destroyed what was known as Black Wall Street.

Walker said his own family suffered a similar fate. "I think some, or all members of my family, you know, left Florida and did so as a result of some sort of things that happened around their ownership of property there," he said.

Kimmerle said it was not uncommon for African Americans to lose their property as cities expanded in the earlier parts of the 20th century.

"What you see all over Tampa, and we could say other cities and places in the country as well, but what you see starting in about the mid-30s—1935, 1936 is the development of the Tampa Housing Authority and other sort of authorities where it’s private business and authorities working together because there was now federal money available," she said.

"So, they start choosing areas to redevelop, and it’s called, very blatantly in the papers and all the records, ‘slum clearance projects,’ she said. "And these areas are targeted for development. But often what you had are Black neighborhoods, and it’s redeveloped into white housing projects and it was very much tied into what becomes redlining of American cities."

Kimmerle said if an area could be designated as a slum or blighted community, it became easier for land to be taken. "People didn’t have a choice. It’s essentially a type of eminent domain. Nor did they have a choice on what the true value of the property would be," she said.

"And so, that starts in the 30s, and the neighborhoods that you see targeted coincide with a lot of these cemeteries that are being rediscovered as having been here," said Kimmerle.

Thomas H. B. Walker owned across the state, and his great grandson says there were hard feelings in his family about what happened to it over time.

"It was always a little confusing to me, but what I could ever get out of my grandfather was that, you know, what we have in Florida was stolen from us by the white man. That was the way he put it," he said.

Walker said learning that his great grandfather's cemetery was eventually redeveloped into homes and a parking lot is not surprising.

“There's not just been this passive suppression of our history,” he said. “There's been very active and purposeful suppression of our history. Even down to things like you know, plowing over a cemetery and building another building on top.”

Walker hopes this discovery will encourage more people to learn more about African American history and its connection to today.

"I think there's a whole history of Black Americans post-Civil War that's been kind of lost," Walker said. "You know, it's only now kind of reemerging, right?

“The truth of the matter is there’s a whole generation of Black folks who are the descendants directly of slaves who actually were entrepreneurial and built businesses and were thriving across the South and across the country. And, you know, particularly with the onset of Jim Crow, all that's been lost...it has been purposefully buried.”

Emerald Morrow is a reporter with 10 Tampa Bay. Like her on Facebook and follow her on Twitter. You can also email her at emorrow@10TampaBay.com. To read more about the search for lost African American cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area, visit wtsp.com/erased.