ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. — Death is tightening its grip on the Gulf of Mexico.

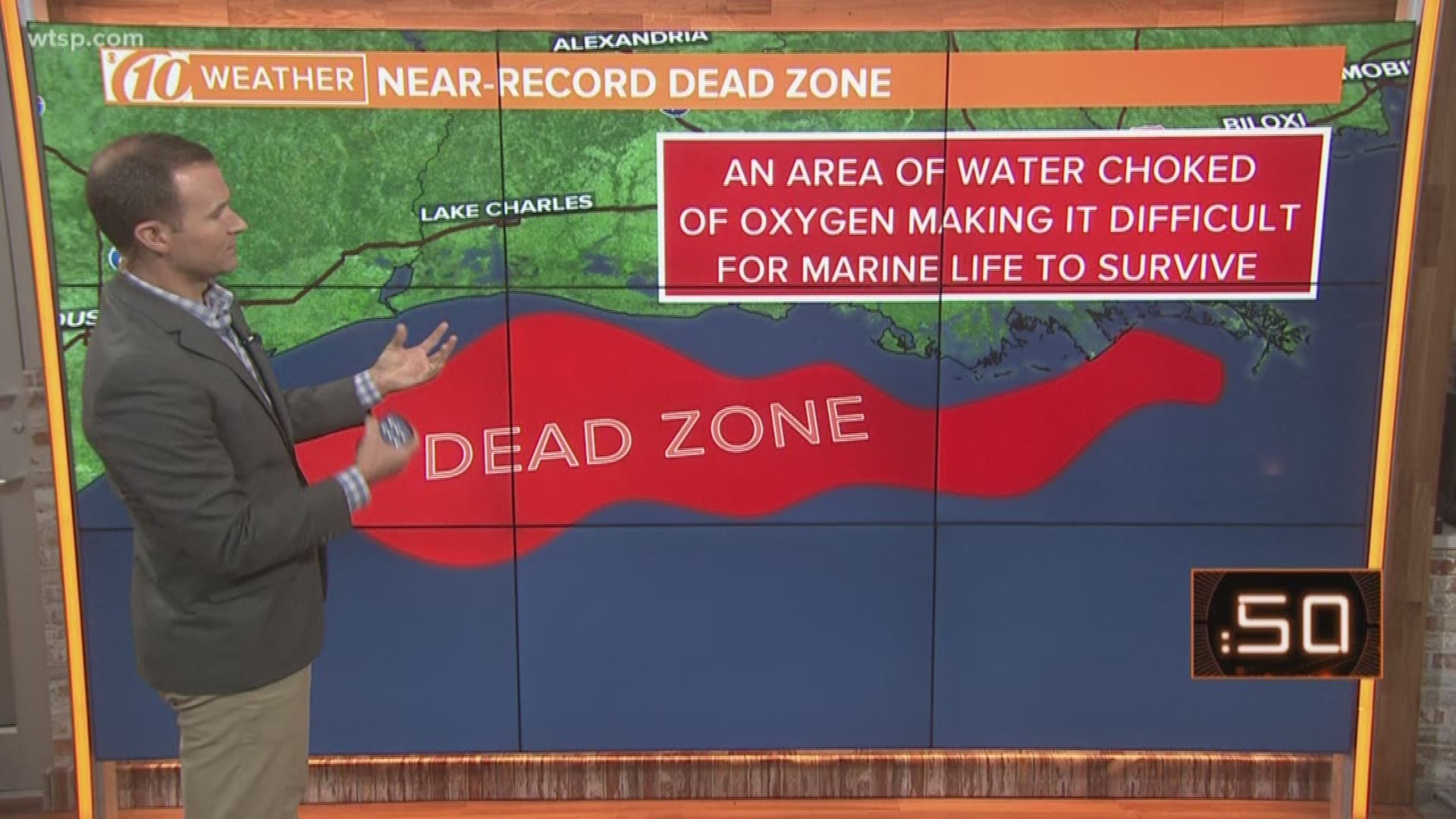

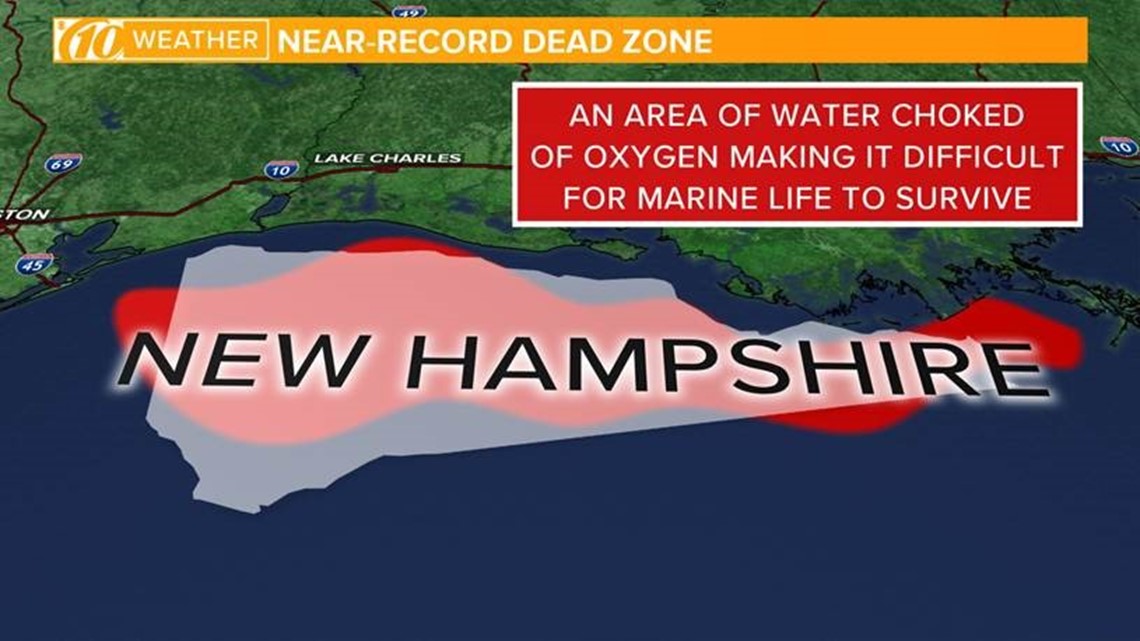

Louisiana State University researchers forecast the summer's hypoxic zone, otherwise known as the "dead zone," in the Gulf of Mexico could expand to an area of about 8,717 square miles. For context, the state of New Hampshire is a little over 9,300 square miles.

The worst hypoxic zone in recorded history reached 8,776 square miles in 2017, and the five-year average is 5,770 square miles.

Almost no marine life exists in this space, which stretches from an area off the coast from about Houston to New Orleans and to the western Florida Panhandle. The "dead zone" -- one of the largest in the world -- reoccurs each year largely from excess nutrient pollution caused by human activity.

This pollution, mainly from agriculture, from the Plains and Midwest eventually makes its way to the Mississippi River and into the Gulf of Mexico. The nutrients spur the overgrowth of algae, which die and decompose in the water. This creates extremely low oxygen levels -- a necessity in supporting marine life.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is citing this spring's "abnormally high amount" of rainfall for the "dead zone" expansion. All of that flooding has to empty somewhere, and it's a straight shot to the Gulf of Mexico.

A bigger "dead zone" is a big deal to life on the water: NOAA estimates it costs the U.S. seafood and tourism industries $82 million a year, and more than 40 percent of the nation's seafood comes from the Gulf.

Scientists believe big -- and potentially larger "dead zones" -- will occur in the future. Thanks to climate change, significant rainfall events across the Mississippi River watershed likely will dump more nutrient pollution more frequently.

"Long-term monitoring of the country's streams and rivers by the USGS has shown that while nitrogen loading into some other coastal estuaries has been decreasing, that is not the case in the Gulf of Mexico," said Don Cline, associate director for the USGS Water Resources Mission Area, in a news release.

What other people are reading right now:

- More reports of sickness and death at resorts in the Dominican Republic

- Helicopter crashes into Manhattan building, officials say

- Tampa will have a 2.5-mile waterfront fireworks display for Independence Day

- Jupiter will be so close in June you can use binoculars to see its moons

- Mother Nature gave this mom-to-be the most dramatic photo backdrop

►Have a news tip? Email desk@wtsp.com, or visit our Facebook page or Twitter feed.